THE STORY OF THE MPABS

aka PsyBari

THE STORY OF THE MPABS

David Mahony, Ph.D., ABPP

In 2000 I was working in a private practice as a clinical psychologist. I received a call from a local bariatric surgeon asking if I could provide psychological evaluations for their patients. I didn't know anything about bariatrics or obesity so I asked them to tell me what types of psychological or behavioral problems they were concerned about. The answer they gave me sent me on a long journey that is still unfolding. Essentially, they said "We don't know, you're the psychologist, why don't you tell us." For those of you that get these kinds of referrals you know that this is not unusual response! Luckily, I enjoy taking on professional challenges so I took on some of their cases.

Many of you may know that back in 2000 very little was known about the psychosocial aspects of obesity and even less was known about the potential complications of bariatric surgery. When I looked for assessment instruments in this area I found none! This was surprising since there were dozens of assessment instruments for anorexia, which affected less than 1% of the US population, but obesity, which affected over 30% of the US population, was largely ignored. Similarly, literature searches found very few publications on the psychological aspects of obesity and bariatric surgery while there were 1000's of reports on anorexia. It seemed that the scientific community had followed the social etiquette of the time -- it's ok to talk about someone that is too thin but if someone is overweight don't say a thing! Even when I looked into the National Institutes of Health's original 1991 recommendation that all bariatric candidates receive psychological clearance there were no explanations for these recommendations. In effect, in 2000 there was almost no scientific data on the psychosocial risks of bariatric surgery. This lack of scientific knowledge, and the lack of a validated assessment instrument, left me in a quandary. On what basis would I evaluate bariatric candidates? What problems should I be looking for? What types of problems did bariatric candidates have after the surgery? The surgeon's office had given me a list of referral questions but these were very not very useful (e.g., "Can the patient handle bariatric surgery?").

The lack of scientific knowledge led me to inquire from the bariatric staff about the types of problems that occurred in bariatric patients. The staff were usually surprised by my questions and assumed that psychologists knew all about bariatric patients or that the problems that bariatric patients had were the same as every other population. They assumed that I had more knowledge than I actually had, were disappointed when I admitted to the deficits of knowledge in this area, and had to be coaxed into telling me about the psychosocial problems they had seen. Over time, staff members began to provide me with anecdotal evidence of post-surgical problems including divorces, increased alcohol use, and the difficulties following dietary restrictions.

Around this time I also began to facilitate post-surgical support groups where I heard first hand about the difficulties that patients experienced with adherence to post-surgical restrictions, changes in relationships, changes in self-image, etc. I also became aware of the amazing power of bariatric surgery. Although many patients experienced difficulties, they also had remarkable weight loss, improved energy, decreased medical problems, and as many would describe it "a new lease of life." As I collected this evidence, I developed a deeper understanding of the psychosocial aspects of bariatric surgery. I saw some of the expected problems, like symptom substitution (e.g., exchanging alcohol for food), but these were minimal in comparison to the problems patients had adjusting to the changes in their relationships. I also saw that patients were happier, more energetic, and often made positive changes in their lives (e.g., new jobs, new relationships, etc.). It was not just the medical problems that were improving but their overall psychological well-being was improving. The fact that the outcomes of bariatric patients varied widely was an important discovery. Since I was trying to identify patients that were at risk for post-surgical problems I also had to understand why some patients showed dramatic improvements. What I discovered was that patients that were able to adjust to their new bodies and make positive changes in their lives (e.g., exercising, improving relationships, getting better jobs, etc.) had fewer problems while patients that were unable to adjust to their new bodies were more likely to have problems (e.g., difficulties with dietary restrictions, depression, alcohol abuse, etc.).

As I continued to acquire anecdotal evidence of the changes that patients experienced I began to develop a questionnaire that assessed all of the psychosocial domains involved in bariatric surgery. Since the goal was to identify patients that were at risk for post-surgical psychosocial problems, and these problems involved a wide array of domains, I included items that assessed a wide range of constructs such as eating habits, emotional intelligence, social functioning, ability to understand and tolerate change, ability to tolerate stress, ability to manage negative emotional states and ability to take responsibility for their emotions, eating habits and relationships. I had to assess the patient's psychological strengths as well as their limitations. Once the questionnaire was completed, I used it as a way to collect information before the patient was interviewed. I quickly discovered that it was a rapid method of collecting information about a patient before I interviewed them. In addition, I discovered that patients were a lot more comfortable filling out a questionnaire then they were answering questions during a face-to-face interview since many of the questions made them feel embarrassed and uncomfortable. This was in important discovery and a principle that I continue to follow: i.e., the more I am able to respect and minimize the patient's discomfort when gathering information about their weight the more they are willing to disclose.

During this time I was also administering other assessment instruments (e.g., MMPI, MCMI, etc.) to determine if they provided any useful results. I discovered that these instruments had significant drawbacks. They were lengthy, which made scheduling difficult since I didn't know how long it would take them to complete the tests. They did not assess constructs related to bariatric surgery such as eating habits, how obesity has affected relationships, etc., which meant that all of that information still had to be collected during the interview. Patients complained about the length of the tests and that the test items were not related to bariatric surgery. In fact, when I interviewed the patients after they completing these tests, they were often irritable and hesitant to engage in the interview. This was another important lesson. Bariatric candidates often have limited frustration tolerance so any questionnaires that are administered have to be brief and focused on bariatric surgery. If not, you will not develop the rapport that is essential in these evaluations.

As the questionnaire that I was developing was becoming more comprehensive, I stopped administering other psychological tests due to the complaints and the lack of insight they provided in regard to the referral questions. Once I eliminated these tests I noticed an improvement in the patient's attitudes during the interview. Not only was I able to collect a lot of information with one questionnaire but since the questions were related to bariatric surgery the patients were less defensive during the interview. In spite of this improvement, some patients were still hesitant to open up in the interview and many remained defensive. At this point I began to realize how much bariatric candidates routinely minimized problems regarding their eating habits and psychological states. Some were adamant that they do not eat excessive amounts of food ("I don't eat that much!") and that they never, ever, not even once, experienced a negative psychological state (e.g., depression or anxiety). It became apparent that this high level of denial and minimization would have to be assessed by the questionnaire. If I was going to evaluate bariatric candidates with a questionnaire I had to know how forthcoming they were about their eating habits and emotional states. Although there are many reasons that patients minimize and deny psychological problems, bariatric candidates had unique reasons for doing so including concerns about receiving surgical clearance and feeling embarrassed about their weight and eating habits. In fact, many patients were so used to minimizing issues in regard to their weight that they often have limited awareness of these issues.

As I learned more about these response biases I began to develop and incorporate items into the questionnaire that would measure these biases. I also realized that biases such as minimization and denial were so prevalent in this population that not only was it important to assess for test validity purposes but it is also a clinical marker (e.g., patients that were unable to acknowledge their eating habits would probably have more difficulties adjusting to post-surgical dietary restrictions). In this way, over time, I began to develop a greater understanding of the idiosyncrasies in this population, a greater depth of knowledge about post-surgical psychosocial complications, and I was becoming more adept at phrasing test items in a way that minimized defensiveness and maximized openness and honesty from patients.

As the questionnaire developed, I was eventually able to collect enough data to do some preliminary analyses. What I discovered in these initial studies was that not all bariatric candidates are equal. Most notably, I identified differences between males and females including the fact that their risk profiles were different (i.e., the risk factors for males were different than the risk factors for females). For example, males were more at risk for problems with irritability and anger while females experienced more problems adjusting to social and relationship changes. This was important since previous to this work bariatric patients were all considered to have the same post-surgical risk factors. I also discovered racial and age differences (e.g., younger patients were making more dramatic life changes after surgery, African-Americans were not as socially ostracized as Caucasians due to weight). Because of these differences, I began to develop separate norms and risk profiles for each group. Around this time the questionnaire also went through a formal validation study. Similar to the results of our previous studies we identified distinct factor structures for each gender.

During the research to validate the MPABS, I discovered that many bariatric surgery candidates that are eligible for the procedure were not going through with the surgery. Since these patients had already received psychological clearance I had data to do some research on this issue. What I found was a surprise. Over 30% of the patients that were eligible for the procedure were dropping out of the surgical process. Given the fact that bariatric surgery is the most effective way to treat obesity, and these patients were usually adamant during the psychological evaluation that they would complete the surgery, this was a surprise. What we found was that patients were dropping out of the surgical process due to their belief that they could lose weight on their own with diet and exercise and they had anxiety about the actual surgery. Using this data I was able to identify the profiles of bariatric candidates that are at risk for dropping out of the surgical process. This information is useful for many reasons. From a clinical perspective it gives clinicians a chance to address these concerns to make sure that the patient is making this decision for the right reasons. Most patients have tried to lose weight for over 20 years before they consider bariatric surgery. If they are now postponing surgery to give diet and exercise "one more chance" it is important to realistically assess their likelihood of success.

These are the highlights of the development of the MPABS. Over time I have learned that bariatric candidates have unique biases that need to be assessed and test items need to be tailored to best minimize these biases; bariatric candidates are not a homogenous group but consist of multiple subgroups with distinct norms and risk profiles; and many candidates will not go through with the surgery in spite of being living with the downsides of obesity for years. My research has continued to discover unexpected results that allow me to learn more about this population. As more studies are completed, future versions of the MPABS will incorporate these findings to make the test more relevant to the idiosyncrasies of this population and more accurate in identifying patients that are at risk for post-surgical psychosocial complications.

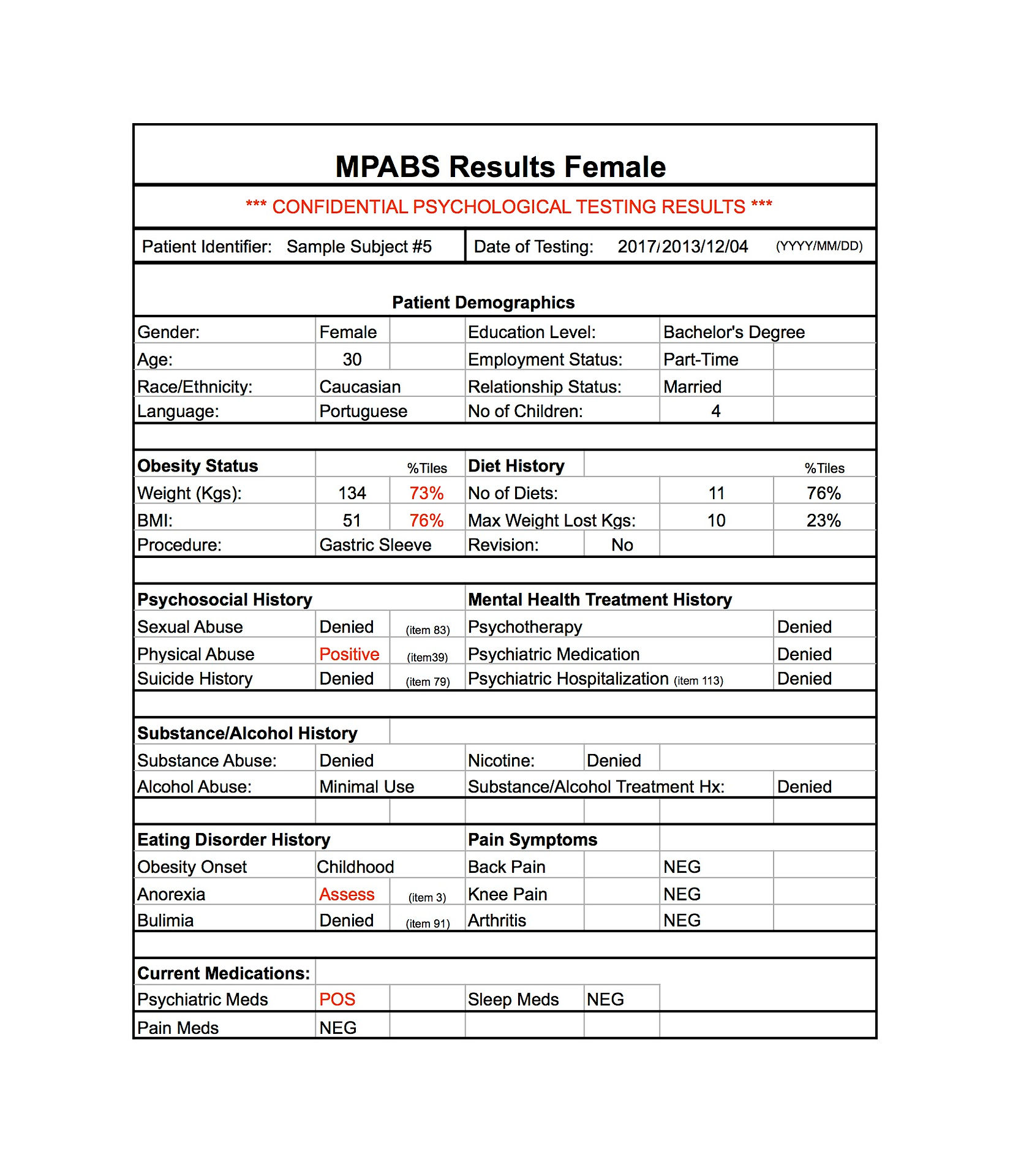

One of the initial goals of the MPABS was to be able to provide on-line scoring. By scoring the test on-line, scoring would be faster, we would be able to update the test regularly to incorporate new research results, and we would minimize scoring errors. Eventually, after many years, a lot of money, and a lot of time, we were able to get a scoring website up and running! The website was tested thoroughly for accuracy and as is often the case software bugs were tediously discovered and corrected over time. The site is now up and running and has performed flawlessly for several years. Users can administer the MPABS, enter the data on the website, and instantly print out the results! Once a user is familiar with the process, scoring takes about two minutes! Another bonus to on-line scoring is we have access to all the data which allows us to perform more research and update the test frequently! For example, we have recently discovered that the patient profiles vary based on country of origin (i.e., bariatric candidates in the US have different norms when compared to candidates in Australia). As the data continues to come in we can continue to identify differences and modify the risk profiles.

Our latest technological advance was to make the MPABS available for tablet scoring! Patients can complete the test on a tablet and the results are sent to the clinician. The scoring is done automatically without any effort from the clinician! We are also in the process of validating the MPABS for Spanish speakers so if you are evaluating Spanish speaking bariatric candidates let us know.

That is a brief version of the story of the MPABS. If you've made it this far I hope you found it interesting. We are attempting to address the lack of psychological assessment instruments for bariatric candidates as well as incorporate technological advances to make test administration and scoring easier. We also hope to be able to update the test frequently. With that in mind, to date, all of the income that we have received from the test has gone back into further developments (mostly the development and maintenance of the scoring website as this tends to be expensive). I have no plans to change this model so rest assured all of the income from administrations is going towards improvements in the test.

Our Team

David Mahony, Ph.D., ABPP, CSO

drdavidmahony@gmail.com (718) 668-1919

Dr. Mahony is a clinical psychologist working in the field of bariatrics since 2000. Dr. Mahony is the author of the MPABS (aka PsyBari) and has published extensively in regard to the psychological profiles of bariatric surgery candidates. His work includes the identification of subtypes of bariatric candidates, candidates that are at risk for post-surgical psychosocial complications, and those that at at risk for surgical attrition.

Mark Whittemore, CIO

Mark Whittemore is a senior software engineer with 30 years of practical experience in all aspects of software design, development,

and Web, and database technologies. After hiring multiple firms, Mr. Whittemore was the only one that succeeding in getting the MPABS scoring site up and running!